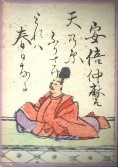

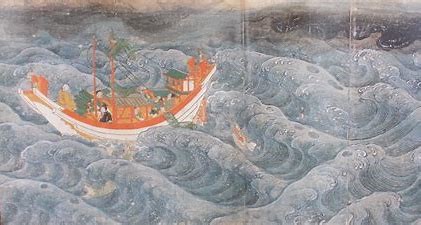

As a Japanese scholar and waka poet of the Nara period, Abe no Nakamaro served on a Japanese envoy to Tang China and later became the Tang duhu (protectorate governor) of Annan (modern Vietnam). He was a close friend of the Chinese poets Li Bai and Wang Wei, Zhao Hua, Bao Xin, and Chu Guangxi. In 717–718, he was part of the Japanese mission to Tang China. In China, he passed the civil-service examination. Around 725, he took an administrative position and was promoted in Luoyang in 728 and 731. In 734, he tried to return to Japan but the ship to take him back sank not long into the journey, forcing him to remain in China for several more years. In 752, he tried again to return, but the ship he was traveling in was wrecked and ran aground off the coast of Annan (modern day northern Vietnam), but he managed to return to Chang'an in 755. When the An Lushan Rebellion started later that year, it was unsafe to return to Japan and Nakamaro abandoned his hopes of returning to his homeland. He took several government offices and rose to the position of Duhu (Governor-protector) of Annam between 761 and 767, residing in Hanoi. He then returned to Chang'an and was planning his return to Japan when he died in 770 at age 72.

During this period, the Emperor Shōmu (AD 701 – 756) who’s reign spanned the years 724 through 749 attached great importance to the well-being of social and economic aspects of everyday people. He believed this could be achieved by providing a stable livelihood for the people. Convinced that the Buddhist faith was a means to ensure both the happiness of the individual and peace/stability for the country as a whole, he introduced strong doses of Buddhism into his government. Furthermore, he aggressively imported knowledge about the Chinese civilization which was the dominant culture of the region by sending diplomatic envoys known as kentōshi to the Tang court every twenty years. On this basis, the Nara culture was not only influenced by China's Tang culture but in turn by Indian and Iranian cultures which highly influenced the Tang Dynasty and its predecessors. Upon abdication, Emperor Shōmu was succeeded by his daughter Empress Kōken, who ascended the throne at the age of 31. She first reigned from 749 to 758, then, following the suppression of the Fujiwara no Nakamaro Rebellion, she reascended the throne as Empress Shōtoku from 764 until her death in 770 which coincided with Abe no Nakamaro’s. Successive rulers saw the decline and internal turmoil which led to the end of the Nara Period and the emergence of the Heian period (Golden Age), a period in Japanese history when the Chinese influences were in decline and the national culture matured

The Nara period with its vigorous promotion of Buddhism, Buddhist culture, especially Buddhist art laid the foundation for Heian period also known as the golden age of Japan.

The Tang dynasty prior to the An Lushan Rebellion from AD 755 to 763 was considered the golden age of Chinese civilization, a prosperous, stable, and creative period with significant developments in culture, art, literature, particularly poetry, and technology. Buddhism became the predominant religion for the common people. Chang'an (modern Xi'an), the national capital, was the largest city in the world during its time. Its cultural influence to its neighbors Korea Japan and Northern Vietnam was substantial. During and after the An Lushan Rebellion and late Tang Dynasty AD 755 to 907 cultural transfers slowed as the Tang Dynasty became unstable and began to decline as the empire was worn out by recurring revolts of regional warlords, while internally, as scholar-officials engaged in fierce factional strife, corrupted eunuchs amassed immense power. Catastrophically, the Huang Chao Rebellion, from 874 to 884, devastated the entire empire for a decade. The sack of the southern port Guangzhou in 879 was followed by the massacre of most of its inhabitants, especially the large foreign merchant enclaves. By 881, both capitals, Luoyang and Chang'an, fell successively

During this period cultural transfers were mainly one way, from China to Japan. Major cultural transfers include rice cultivation, writing/script, Buddhism, centralized government models, civil service examinations, temple architecture, clothing, art, literature, music, and eating habits

Between the Late Tang Dynasty of China and the Heian period of Japan, is a period in Japanese history when the Chinese influences were in decline and the national Japanese culture matured. In the way that China adapted Indian Buddhism, Japan adapted the Chinese form of Indian Buddhism. While in literature the golden age of Japanese literature flourished as they moved away from Chinese characters and began using phonetic based scripts (hiragana and katakana) which was easier for the common people to learn.

The primary influence on the cultures of China and Japan during the latter centuries of these periods were determined by their respective policies toward cultural and trade relations with western nations.

After a century of instability between late Tang and Early Song, The Song Dynasty became the second ‘Golden age’ when peace and stability was achieved. Technology, science, philosophy, mathematics, and engineering flourished during the Song era. The Song dynasty was the first in world history to issue banknotes or true paper money. After the Song Dynasty collapsed the only major non foreign dynasty ruling China was the Ming Dynasty and its major cultural contribution of porcelain and its artistic styles. During the latter decades of the Ming Dynasty and the throughout the Qing Dynasty, cultural isolation from the west was the general policy. The Hăijìn (海禁) or sea ban was a series of related isolationist policies restricting private maritime trading and coastal settlement during most of the Ming Empire and early Qing Empire. Despite official proclamations the Ming policy was not enforced in practice, and trade continued without hindrance. The early Qing dynasty's anti-insurgent "Great Clearance" was more definitive and had devastating effects on communities along the coast. During these periods China was greatly weakened as innovation and knowledge from the rest of the world was stifled.

Sakoku literally ("chained country") was the isolationist foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countries were severely limited, and nearly all foreign nationals were banned from entering Japan, while common Japanese people were kept from leaving the country.

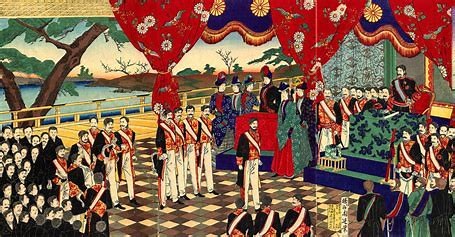

The trigger for the reversal of the Sakoku policy was the Opium Wars (1839-1860) in China between the Qing dynasty and Western powers in the mid-19th century. The Japanese knew they were behind the Western powers when US Commodore Matthew C. Perry came to Japan in 1853 in large warships with armaments and technology that far outclassed those of Japan. Shimazu Nariakira a renowned feudal lord, concluded that "if we take the initiative, we can dominate; if we do not, we will be dominated", leading Japan to "throw open its doors to foreign technology. This new opening up and embracing western culture and technology is known as the Meiji Restoration period (1868–1931).

Cultural transfers between China and Japan were limited during this time due to both countries pursuing various isolationist policies. One major transfer of culture was porcelain and art styles of porcelain from China to Japan and to the rest of the world during the Ming Dynasty.

Following the collapse of an isolationist Qing Dynasty along with instability caused by factional fighting among warlords, western culture and technology began to be absorbed via Chinese scholars studying abroad. After the conclusion of World War 2 and the Chinese civil war, a period of isolation occurred other than with the Soviet Union. During this time traditional Chinese culture was displaced by communism during the Cultural Revolution 1966-1976. After the reopening of China under Deng Xiaoping China’s modernization was accelerated by heavy investment and trade with Japan. With the opening of the economy and an end to isolationism literacy increased with the use of pinyin and traditional Chinese culture and values began to return.

After its loss in World War 2 and the occupation of Japan by American forces until 1952, Japanese culture rapidly westernized.

Influential cultural transfers during this time include cuisine such as sushi to China, and the modern Eight Cuisines of China to Japan: Anhui (徽菜; Huīcài), Guangdong (粤菜; Yuècài), Fujian (闽菜; Mǐncài), Hunan (湘菜; Xiāngcài), Jiangsu (苏菜; Sūcài), Shandong (鲁菜; Lǔcài), Sichuan (川菜; Chuāncài), and Zhejiang (浙菜; Zhècài). Outside of cuisine, transfers from Japan to China include Japanese style animation and Japanese loan words to China.

For instance, ‘telephone’ was directly translated into three syllables at first, 德律风 dé lǜ fēng, which was difficult to remember and understand the meaning. Democracy was translated into 德谟克拉西 dé mó kèlā xī. This word with five syllables is very long and not normal in modern Chinese. Therefore, many long and meaningless western loanwords were replaced by Japanese loans. 德律风 dé lǜ fēng was replaced by 电话 diàn huà, 德谟克拉西 dé mó kèlā xī was changed into 民主 Mínzhǔ, which are more understandable to Chinese people.

电视[diàn shì] meaning “television” comes from the Japanese 電視(でんし) [denshi]

杂志[zá zhì] meaning “magazine” comes from the Japanese 雑誌(ざっし) [zasshi]

电话[diàn huà] meaning “telephone” comes from the Japanese 電話(でんわ) [denwa]

自由[zì yóu] meaning “liberty” comes from the Japanese 自由(じゆう) [jiyū]

电池[diàn chí] meaning “battery” comes from the Japanese 電池(でんち) [denchi]

投资[tóu zī] meaning “invest” comes from the Japanese 投資(とうし) [tōshi]

社会[shè huì] meaning “society” comes from the Japanese 社会(しゃかい) [shakai]

系统[xì tǒng] meaning “system” comes from the Japanese系統(けいとう) [keitō]

温度[wēn dù] meaning “temperature” comes from the Japanese 溫度(おんど) [ondo]

In a nutshell, Japanese has absorbed Chinese since the ancient times and made Chinese characters into their own writing system. After its modernization, Japanese invented lots of words with western meaning in Chinese characters and then introduced and exported them to China, which has enabled China to know about the world, learn new things from the world and keep up with the world.

It is clear that since Abe no Nakamaro both countries benefit and prosper from each other when there is peace and stability and non-isolationist policies. This can be achieved through increased people to people educational exchanges. During the decade 2010-2020 there was an ever-increasing number of Japanese students in China and Chinese students in Japan. At the end of 2019 there were roughly 140,000 Chinese students studying in Japan and 15,000 Japanese students studying in China. Both countries prospered financially and socially. This trend was heavily reversed due to the global covid pandemic (2020) as students remained in their home country. It is our belief that the governments of both countries should financially subsidize the return of these cross-cultural student studies so that both countries can once again benefit and prosper from the mutual understanding of each other’s culture.